Vaccinations have been proven time and time again to prevent

disease and improve health outcomes. All around the world, vaccines have been

deployed to deal with illnesses as common as the flu and as deadly as Ebola. Meningitis

is another disease for which vaccination has become a major priority. The

“kissing disease,” at it is sometimes called, has made a number of appearances

on college campuses across the United States. While incidence in the U.S.

remains quite low, at 0.3-4 cases per 100,000 persons, incidence can be as high

as 1 case per 100 persons in the “meningitis belt” of Africa, where epidemics

occur with regularity.

|

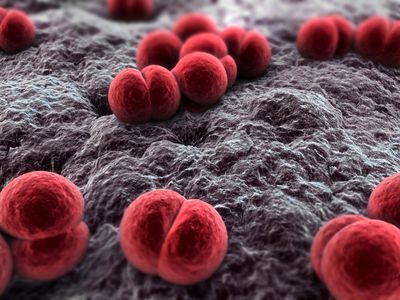

| Neisseria meningitidis, the bacterium responsible for meningitis. Image from Bioquell.com |

Infection with the bacterium Neisseria meningitidis, the major cause of meningitis, often goes

unnoticed. The bacteria take up residence within the nasal cavity, where they can

stay without causing disease in a carrier individual. However, in approximately

1-5% of people exposed to the bacteria, invasive disease occurs, and the

bacteria enter the bloodstream, leading to life-threatening disease.

Symptoms of meningitis typically begin almost immediately,

just one day after infection, and include flu-like symptoms of fever, headache,

and stiffness. Because the bacteria enter the bloodstream, any organ or tissue

can become infected and impaired. Despite years of research, mortality rates

continue to range from 10-15%, even in developed countries, with rates above

20% in the developing world. Even for those who survive the invasive disease

stage, meningitis causes lasting impairments in 19% of patients, with

neurological disabilities, seizures, hearing or visual loss, and cognitive

impairment being classical manifestations. The rapidity of disease progression,

along with the high mortality rate, make meningitis a prime disease target for

vaccination.

The first vaccines against meningitis were developed in the

1970s. Unfortunately, these early vaccines lacked the ability to maintain

long-lasting immunity against the bacteria. In the late 1990s, alterations were

made in the vaccine components, allowing for the elicitation of an

immunological memory response that would be effective to protect young children

into their adult years and would even help reduce the rates of carriage of the

bacteria in the nasal cavity. While this was great news for the prevention of

meningitis, challenges still remained. The bacteria that cause disease can

belong to any of 6 different serogroups, meaning that immunity to one serogroup

will not necessarily provide protection from another. This requires

differential targeting of all 6 serogroups to truly prevent disease.

|

| Image from the Meningitis Vaccine Project |

Researchers have addressed this challenge by producing different

vaccines for use in specific parts of the world where each serogroup is

problematic. In the meningitis belt of Africa, for example, serogroup A has

historically been the cause of epidemics. To wipe out these epidemics, a mass

vaccination campaign was begun in 2010; the Meningitis Vaccine Project produced

and provided vaccines against N.

meningitidis serogroup A for over 217 million people in 17 different

countries. Thanks to these vaccines, epidemics linked to the serogroup A

bacteria have been eliminated.

Unfortunately, when one serogroup is removed, a niche opens

up for another. Just last month, the CDC announced that a small epidemic in

Liberia had been caused by the N.

meningitidis serogroup C bacteria. Nigeria and Niger have also reported

outbreaks of this serogroup. Luckily, in the case of Liberia, the country’s

response time was extremely rapid. Thanks to the health system improvements

made during the Ebola outbreak, Liberia now has a robust case detection and

monitoring system. Other countries in the area, however, are not nearly as

advanced and could suffer a severe epidemic if serogroup C moves in with force.

Great strides have been made in the fight against meningitis

outbreaks. However, the complexity of the group of bacteria responsible for the

disease leaves a number of challenges in place that must be overcome. The ideal

solution would be the introduction of a vaccine that combined pieces from each

bacteria serogroup to produce an immune response in patients that would protect

from all six serogroups at the same time. While some quadrivalent vaccines

already exist, which provide protection against four of the six serogroups,

these vaccines have only been recommended for use in the U.S. for adolescents

entering college. Protection from this vaccine only lasts 2-5 years in adults,

making it less than ideal for deployment in rural areas where boosting is not a

viable option, such as Africa. Advances in vaccine technology may help improve

the longevity of protection, making multivalent vaccination a more robust

solution to the meningitis problem. Until then, rapid case detection and

monitoring capabilities, such as those displayed in Liberia, will be the key to

keeping meningitis epidemics in check as they arise. Between vaccine and

monitoring advances, meningitis epidemics may one day become a thing of the

past.